The works presented on this website from the two collections probably should be understood as emanations of the ‘acrylic painting movement’ that began at Papunya in 1971 with the painters of what became Papunya Tula Artists, the first Indigenously owned art cooperative in Australia. For the most part, it is possible to consider these paintings as almost a spiral of development, outwards from the Papunya beginning to spread to other Indigenous communities with some connection to this starting point.

The collections record mostly two separate moments of artistic work. The Wilkersons’ collection focuses very closely on works of an early period in Papunya Tula painting, works in which one might see some of the early experiments and developments of painting on two-dimensional surfaces of different size. Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield’s collection is mostly focused on works that were produced after that starting moment, and it continues into works produced very recently. In historical time, perhaps with the exception of Sally Gabori’s work and Richard Bell, the works in both collections emanate from a single, basic cultural tradition of image, decoration, and performance and, more specifically, from an historically emergent art movement among Indigenous Australians that has drawn on that tradition. There are paintings from several different Indigenous communities and speakers of different languages, but their underlying cultural forms are shared. That would include the paintings from the Kimberleys, such as Paddy Bedford, and the work from Utopia, such as Emily Kam Kngwarrey.

What is called the "Western Desert art movement” began concretely in 1971 with Indigenous Australian men who were living at a government-managed community in Central Australia known as Papunya. These men developed the practice of painting with acrylics on a two-dimensional surface, eventually Belgian linen, drawing on their own pre-existing practices, images, and their imaginations of ritual and ancestral creative activities in the landscape. They were, I was told very early on, “true” – that is, drawing their authenticity from the ancestral stories that they continued to represent, and the places in the landscape in which they were primally enacted and which were formed by them. Place, story, origins – all inspired the first generation of painters to put their images into two-dimensional form to show to outsiders. This transformation – from body and ritual painting, rock art and sacred objects to two-dimensional forms – was from the beginning a creative invention, a transposing of traditions into different and new forms, striking for their beauty and variety.¹ One would be misled to refer to this as either traditional or non-traditional; that is quite beside the point. The paintings are strongly asserted to be drawn from, inspired by, and transmitting the authority and truth of the ancestral revelations in place, notwithstanding the human variety of creative mediations, instantiations of “truth.”

Such artworks are part of a history, a movement of aesthetic and conceptual development that has changed its forms from its beginnings in 1971 to the present. This movement has been a surprising and inspiring history of invention, innovation, and novelty that has made its way onto museum and art gallery walls throughout Australia, Asia, Europe, and the US – all the more compelling for the fact that many of its creators began their lives as hunting and gathering people in one of the world’s most demanding desert environments.

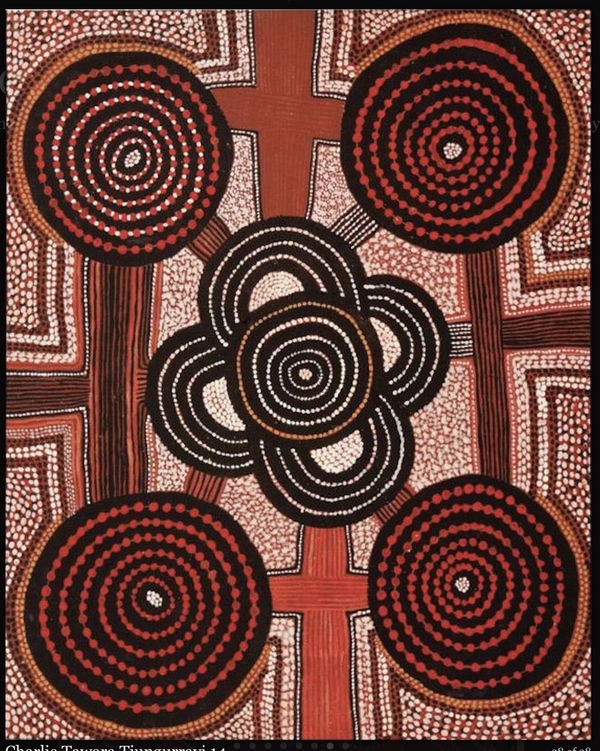

If the Wilkersons have focused on works from the earliest period, the works in Martin and Stringfield’s collection belong to what might be seen as a third or even a fourth wave of innovation.² They were painted by men who were middle-aged in the early 1970s; women of an age in which they might have been married to those men; men who were young in the early 1970s; and a still younger generation. From the works of a second generation of painters, including Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, but especially in Ronnie’s virtuosic range of experimentation across various paintings, one can see a line of change leading to the celebrated, highly abstract works of Charlie Ward Tjakamarra, George Ward Tjungurrayi, George Tjungurrayi and, ultimately, Warlimpirrnga, along with his close female relative Yukultji Napangati and their fellow Kiwirrkurra resident Doreen Reid Nakamarra, too early deceased. It is not hard to see how Warlimpirrnga’s painting Maruwa (2013) draws on the same form that Ronnie developed: the concentric rectangle. Because they use abstract forms, these images are not restricted from being viewed by outsiders.

This information might be useful when looking at their works as part of a history: the virtuosity of these artists cannot be appreciated just because of their passing resemblance to other formalist conventions in modern and contemporary art. These are inventions that tookplace indigenously as Indigenous artists have sought to attract broader public attention and communicate what matters to them through visual art.

I have written extensively about some works in the Wilkerson collection, some of them documented personally by me when they were made (Myers and Smith 2024), and the catalog Icons of the Desert (2009) is dedicated to this collection. On the website, they are showing here some of my favorite paintings. This includes what many people call the ‘masterpiece’ of early Papunya painting, Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula’s “Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa, 1972”, for which I recommend reading John Kean’s Dot, Circle and Frame: the Making of Papunya Tula Art, published in 2023. But for this essay, I am going to offer a discussion of a few paintings that might suggest the depths of the visual imagination one can find in them. The first will be Wartuma Tjungurrayi’s “The Trial”.-

-

-

Doublings: Making a Cosmology Visible

In thinking about what an informed vision might see in the early and later paintings, I offer some thoughts on the special aesthetics that I am calling “Doublings.”“Everywhen” is one of the words that the anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner used to help translate Indigenous understandings of a pervasive world view in Australia that he described in his famous essay “The Dreaming” (Stanner 1956). This phrasing has come to be in more general usage, and was the title of Stephen Gilchrist’s superb exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums in 2016. “Everywhen” draws attention to the continuing (usually unseen) presence of the ancestral realm which is not simply a period that ended in the past. Many people who learn of classical Aboriginal understandings struggle with this violation of Western temporality as typically grasped in the European framework.The Australian anthropologist Mervyn Meggitt, who wrote of the Warlpiri in the 1950s, was led to discuss this structure by drawing on concepts from the 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, as a contrast between a “noumenal” realm and a “phenomenal” one (Meggitt 1972). The Pintupi painters I knew first in the 1970s insisted their paintings were “tjukurrtjanu,” that is “from the Dreaming.” They were not made up by humans. They were true. They explained the features of their paintings by recourse to narrating the travels and activities of the Ancestral Beings, and told me how those activities were embedded in, transformed into, features of the landscape, places they knew and had visited, places where their own spirits had been left behind and from which they were conceived and born. At Kuntarrintytjanya, a man I knew had been left behind, Tjukurrpa. There he sat, he sat, and (eventually) “yurtirringu.” Yurti is a word that means many things in Pintupi. Most simply, we would understand it as “visible.” A bag hung on the branch of a tree is “yurti.” Over there, someone might say, the bag is “yurti.” You can see it. Common word in Pintupi everyday speech. Later, I learned it also can refer to other modalities of sense experience, Sitting in camp at Yayayi with Benny Tjapaltjarri, the subject of the film “Benny and the Dreamers,” he told me a motor vehicle was coming. He could hear it, in the distance: “Yurtirringu (it became yurti)” he said. “You can hear it.”When men reveal ceremonies to initiates, they say they are “showing them” – Yurtininpa means “to show, to reveal, to make sensorily present.” To bring something into the sensory field of others. When a baby is conceived, when the mother realizes she is pregnant, this event is explained as the person “yurtirringu” – literally came into the sensory field. Presumably, this is what Meggitt tried to explain by the concept of a noumenal realm, outside of sensory presence but ultimately informing it. The baby’s spirit, it’s Dreaming, was ‘sitting, Tjukurrpa. Yurtirringu.” It moved from that state into sensory presence… It is not a word referring to magical activity, but an ordinary word, but it is crucial to understanding what Pintupi comprehend through the concept of Tjukurrpa, The Dreaming.So, when I heard a story being told in Pintupi, as I tried to understand what was being said, sometimes I asked – or, better, I learned to ask – “Tjukurrpa nyurra watjarninpa? (literally, is that Tjukurrpa you are telling?). The answer might be, Yes – that this was a Tjukurrpa narrative, about the ancestral beings. Or, I might be informed, “Tjukurrpa wiya. Yurtina watjarnin. Not Tjukurrpa. I am telling (a story) that is Yurti.” That would mean this was a narrative about things that everyone could witness. It was not that sometimes Pintupi didn’t actually “see” Tjukurrpa. Sometimes, in dreams typically, people saw “something” which they realized was a revelation, a showing, of The Dreaming. They learned songs or dances that they understood as “Tjukurrpa.” Or uncanny events or experiences which, often after consideration with others, they came to understand as “Dreaming.” In this way, I have come to think, TheDreaming is still present, but not ordinarily “yurti” unless brought into the sensory world either by extraordinary experiences or by the concerted action of those entrusted with the stories, rituals, and songs left behind by the Ancestral beings.But this means that The Dreaming is not simply a closed book, entirely of the past. Experientially, it can still be there.“Everywhen” refers to this kind of collapsing of time. And thinking about this in the light of the paintings from the Papunya Tula Artists in these collections gave me pause for thought about what I was seeing, what I was being shown in some of them.In 1971-72 a new practice of painting and forms emerged at Papunya. It is a well-known story (see Myers 2002, Johnson 2010, Benjamin 2009), but worth repeating, how senior men from a variety of linguistic groups gathered at the government settlement of Papunya began – in association with the artist-schoolteacher Geoffrey Bardon – to take up the practice of painting. In the new medium – rectangular flat surfaces rather than bodies or objects – the painters drew upon the iconography, ritual practices and decorative forms of their ceremonial life, and the mythological traditions invested in the sacred places they knew as their “country”. The new practice of painting attempted to transform this wide array of knowledge, imagination and embodied experience – musical, performative, decorative, multi-dimensional and restricted – into a two-dimensional painted surface. In the two collections, interestingly, one can find something of a progression in that Papunya history from early works on paper to rather remarkable optically stunning works in acrylic.While not curatorially marked in the website, the work strikes me as illuminating a rather significant theme – of doubling. [Some of the early works, such as John Kipara Tjakamarra’s “Old Man Story” 1972 , are more or less direct transpositions onto the surface of a Tingarri body design, which would have been done in red ochred concentric circles. [I am pretty sure this is a painting of the Tingarri story at Kirritjinya.] These body designs, worn by contemporary ritual performers and initiates on their torsos, are understood to be the same as those worn by the Ancestral Tingarri men in The Dreaming, but also they represent the features of the landscape which the activities of these Ancestors brought forth. Worn on the person, they are also – in some way – part of the land, the place, itself. For the painters, these were not simply ethnographic representations of body designs, because – as I know from inquiring about similar images in acrylic paints – the forms (circles, lines) are themselves iconic representations of ancestral activity and the place it made. -

![Shorty Lungkarta Tjungurrayi, Children’s Water Dreaming (Version 2) [formerly Water Story], 1972](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

-

![Mick Namararri Tjapaltjarri, Big Cave Dreaming with Ceremonial Object [formerly Untitled], 1972](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

-

Historical Trajectories

When we turn to the Martin and Stringfield collection, there is a greater and wider historical story, but we can the painters of Papunya Tula Artists, in works that mostly date after the movement of the principally Pintupi painters of the cooperative back to their own country in 1981. Despite the passage of time and the movement towards more ambiguous and abstract forms, the focus or the paintings continues to be ‘The Dreaming’ and the country (ngurra) in which it is manifest but the visual form in which these truths are made manifest have been subject to continued invention and creativity. We see in the collection some of the developments shown in the work of the first generation male artists, who had lived in their countries as hunter-gatherers and had very direct experience of it and engaged the project of painting with primarily the precedent of traditional body and ceremonial decoration, the innovations of a second generation or wave of men painting, and the inspiration of a third wave – of senior women taking up painting in the early 1990s (see 2021). The trajectory of stylistic change is towards a less overt reference to specificities of knowledge revealed and an attempt to express the power of The Dreaming through optical means, like the flash of ritual designs in the firelight – more indexical and less iconic. As a senior man recently explained, in this way they avoid conflict about who has the right to reveal stories and about what might be revealed publicly. They stay on the surface of their stories, but nonetheless these same paintings are redolent with the memories and histories of relatives who are known through these places and the ancestral identities embedded in them. -

The Artists

Looking Through the Martin-Stringfield Collection -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Acknowledgements

Portions of this essay were taken from essays I have previously published, especially “Doublings” from the Everywhen catalog, also from an essay for Gagosian Quarterly but this essay is now its own thing. -

References

Bardon, Geoffrey and James Bardon2004 Papunya: A place made after the Story. Melbourne: Miegunyah Press.Benjamin, Roger2009 The Fetish for Papunya Boards. In R. Benjamin w. A. Weislogel, eds. Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya. Pp 21-50. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.R. Benjamin w. A. Weislogel, eds.2009 Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya. Pp 21-50. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.Biddle, Jennifer2025 Emily Kam Kngwarray (a review). Visual Anthropology ReviewCole, Kelli, Green Jennifer, and Perkins, Hetti, eds.2024 Emily Kam Kngwarray. National Gallery of Australia.Gilchrist, Stephen2016 Everywhen: the Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia. Harvard Art MuseumsJohnson, Vivien2009 “The Intelligence of Pintupi Painting.” In R. Benjamin w. A. Weislogel, eds. Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya. Pp 65-70. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.2010 Once Upon a Time in Papunya. Sydney: New South Wales Press.Kean, John2023 Dot, Circle and Frame: the Making of Papunya Tula Art. Upswell PublishingKennedy, Randy2015 An Aboriginal Artist’s Dizzying New York Moment. New York Times, Sept 18, 2015.Meggitt, M.J.1972 Understanding Australian Aboriginal society: kinship systems or cultural categories. In P. Reining, ed. Kinship Studies in the Morgan Centennial Year. Washington, DC. Anthropological Society of Washington.Myers, Fred1986 Pintupi Country, Pintupi Self: Sentiment, Place, and Politics among Western Desert Aborigines. Smithsonian Institution Press, Wash., D.C. (reprinted in paperback by University of California Press, 1991)2002 Painting Culture: The Making of an Aboriginal High Art. Durham: Duke University Press.2009 “Graceful Transfigurations of Person, Place and Story: The Stylistic Evolution of Shorty Lungkarta Tjungurrayi.” In Roger Benjamin, ed. Icons of the Desert. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Pp. 51-64.2014 “Showing Too Much or Too Little: Predicaments of Painting Indigenous Presence in Central Australia.” In Glenn Penny and Laura Graham, eds. Performing Indigeneity. University of Nebraska Press. Pp 351-389.2021 “The Goannas Are Dancing: The Generation and the Generations of Papunya Painting.” In Myers and Skerritt, eds. Irrititja Kuwarri Tjungu (Past and Present Together): Fifty Years of Papunya Tula Artists. University of Virginia Press. Pp 25-35.2024 “Papunya Tula Artists – Paintings, Turlku, Corroboree, Story,” in M. Langton and J. Ryan, eds. 65000 years of Australian Art History. Melbourne: University of Melbourne Press. Pp 253-267.Myers, Fred and Terry Smith2024 Six Paintings from Papunya: a Conversation. Duke University Press.Scholes, Luke, ed2017 Tjungunutja: From Having Come Together. Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory.Stanner, W.E.H.1956 The Dreaming. In T.A.G Hungerford, ed. Australian Signpost. Melbourne: Cheshire.Strocchi, Marina2021 Family Connections: Walugnurru Women in Action. In Myers and Skerritt, eds. Irrititja Kuwarri Tjungu (Past and Present Together): Fifty Years of Papunya Tula Artists. University of Virginia Press. Pp 267-78

![Shorty Lungkarta Tjungurrayi, Children’s Water Dreaming (Version 2) [formerly Water Story], 1972](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_620,h_620,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-twocollections/usr/images/artworks/main_image/items/5f/5f1c4f9b70c7461588df97e635aeb974/cat24_sltjungurrayi.jpg)

![Mick Namararri Tjapaltjarri, Big Cave Dreaming with Ceremonial Object [formerly Untitled], 1972](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_620,h_620,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-twocollections/usr/images/artworks/main_image/items/37/3788543d4a8d456a97b9380140359bf0/cat32_mntjapaltjarri.jpg)