This knockout show at Tate Modern is the first large-scale solo exhibition of Kngwarray’s work in Europe. All created when she was in her seventies, the Australian’s paintings astonish.

By the time she died in 1996, at about the age of 80 (her birthdate is hazy), Emily Kam Kngwarray had created somewhere in the region of 3,000 paintings. That these were all made in the last eight years of her life is not even the most remarkable thing about this titan of Australian art.

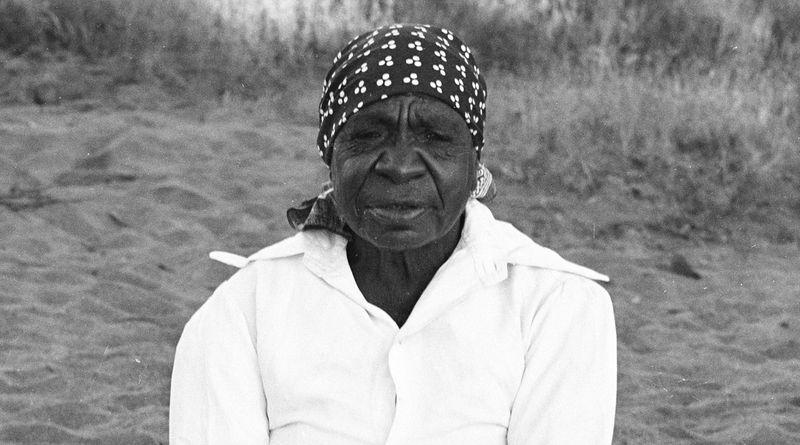

A senior Anmatyerr woman from the Sandover Region of the Northern Territory, Kngwarray is one of the country’s best-known artists, Aboriginal or otherwise. But this stunning show at Tate Modern is the first large-scale solo exhibition of her work to be mounted in Europe.

She started experimenting with art at Utopia Station (Utopia is the former name of the Aboriginal homeland where Kngwarray spent her life) alongside other women of her community, first with batiks, a number of which are on display, and then, from the late Eighties, acrylic paintings on canvas. And my goodness, she was good.

These works are so compelling. They seem to teem with life, even when you’re not sure what you’re looking at (perfectly possible, especially at first). Kngwarray’s art is firmly rooted in her ancestral lands; it is an extension of cultural traditions specific to her people and can feel a bit baffling as your eyes roam around the intensely busy surfaces, thronged with dots and lines, wondering what you’re supposed to be seeing.

A tip: in number six of the ten rooms of this show there is a short film in which several women of Kngwarray’s community hold an Awely ceremony, grinding pigments and painting their bodies, before singing and dancing and talking about “the old woman”, as they describe Kngwarray. These visuals, along with aerial shots of the surrounding country, are incredibly helpful to get your eye in a bit on what she’s depicting or evoking — I’d head straight there first, then whizz back to the start.

Curators do a grand job of filling in enough of the background to help you to feel grounded; the wall texts, which are the clearest and most informative I’ve seen at Tate in quite some time, briefly explain concepts like Country (the particular lands, skies and waters to which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are deeply connected); the Dreaming, or Creation Time; and Dreamings, which are ancestral beings, manifest in the life forms of Country — emus and pencil yams are two examples that are particularly important to Anmatyerr culture, and evocations of them appear repeatedly throughout the work, even as Kngwarray’s style shifts and evolves.

But even without understanding their origin (and it’s clear there are layers to this that western viewers, with our grievous disconnection from the land, are not equipped to grasp, which does confer an oddly elegiac quality), most of these paintings are just fantastic. They have a vitality, a dynamism, a beauty, depth and complexity that sets them apart. As the women say, “the Country transforms itself and those paintings do as well. That’s why the old woman is famous.”

By Nancy Durrant